South Colton Oral History Project offers glimpse of 1890-1970 Mexican society

5 min read

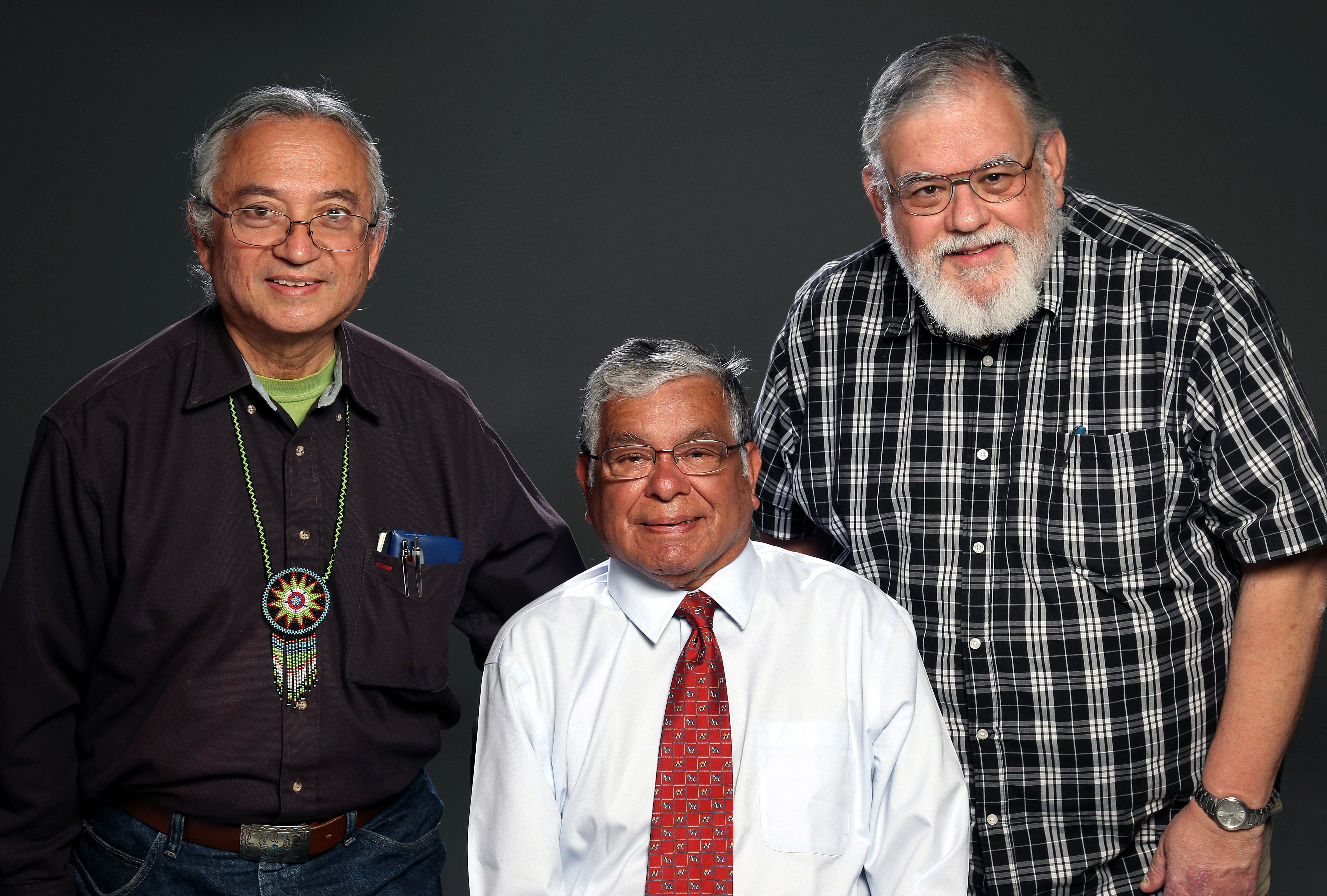

The South Colton Oral History Project, a collaborative effort of Cal State San Bernardino Pfau Library, California Humanities Foundation and the Colton Area Museum, is led by a three-member volunteer research team of retired educators, pictured from left, Henry J. Vásquez, Dr. Tom Rivera, and Frank Acosta. The project is producing a record of life in South Colton, a 1.3 square-mile ethnically segregated Mexican American community in the era from 1890 to 1970. Interviewees are life‐long residents of the area whose parents or grandparents settled there during the study’s time period. In digitally recorded interviews, they shared personal stories and perceptions of life in South Colton. 25 of the 70 recorded interviews have been transcribed and available to the public.

Racism, segregation and poverty characterized Colton from the 1890s through the mid 1950s, yet a small Mexican community in the southern part of the city thrived amid culture, family and self-sufficiency.

The 1.3-square-mile area, referred today as South Colton, was rich in history and heritage, yet there are very few, if any, recorded accounts of the “Mexican” side of town.

As the older generation who lived during the turn of the 20th century started to perish, the history of South Colton was at risk of disappearing. Dr. Tom Rivera, eager to fill in the historical blanks and record the stories of the community, collaborated with fellow retired educators Frank Acosta and Colton native Henry J. Vásquez to interview those who lived in the community from 1890 – 1970.

“Time is the enemy of any study attempting to capture what is ‘locked up in the minds of the few,’ for each passing day, those few become fewer and fewer,” stated Dr. Rivera, a South Colton native. “Many of the potential interviewees already identified for this project are in their 80’s, a handful are in their 90’s and 13 have passed away. In South Colton’s case, there are few historical records that can offer insight into what life was like for past generations.”

The ongoing South Colton History Project was initiated in 2013 with the support of Cesar Caballero, Dean of the California State University, San Bernardino Pfau Library.

To date the trio has conducted over 70 interviews, one hour to one-and-a-half hours in length. 25 of those videos have been successfully transcribed and are now available to the public at http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/colton-history. More interviews will be available as they are transcribed.

“Historians refer to newspapers to study a community’s history, and the only stories written about South Colton were about people robbing places, or other crimes,” said Dr. Rivera. “It wasn’t an accurate portrayal of the people who lived there… we were dedicated people, solid, hardworking citizens who contributed to our community.”

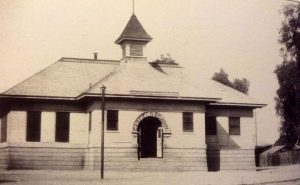

The Southern Pacific Railroad severed the city in half – to the north of the tracks lived the whites, to the south the Mexicans. A snapshot of life during that time included a curfew imposed on Mexicans barred from the white side of town past a certain hour; segregation of schools – Mexicans attended Garfield Elementary (now Wilson) and Wilson Jr. High until integration occurred during the 1953-54 academic year when Roosevelt Jr. was renamed Colton Jr. High; boys in high school were encouraged to drop out, whereas the girls enjoyed its freedom and social opportunities; main employers were the railroad, Pacific Food Express, the cement plant and the citrus industry; local commerce included bakeries, grocery stores, barber shops, gas stations, a shoe store, dance hall, night clubs and liquor stores.

According to Acosta a common thread that ran through many of the interviews were the strong ties to churches. A person of influence during the time was Father Valencia of San Salvador, the first Catholic Church established in South Colton.

“There were also Protestant churches, such as La Iglesia Bautista, whose members were referred to as ‘aleluyas’ by the Catholics,” revealed Acosta.

Another prominent figure was entrepreneur Juan Caldera who established the first sports complex in the community.

“He built it in response to prejudice, Mexicans couldn’t use their (white’s) pools or facilities, so he built the second largest pool in California, a bullring, boxing ring and baseball stadium,” Acosta disclosed. Athletics would bring the different races of Colton together.

Many of those interviewed attributed sports to having played an important role in integration, as well as being a source of pride and accomplishment. Early baseball teams sponsored by local businesses included mixed ethnicities and races.

Racism at the time extended to property – Mexicans were prohibited from buying homes on the north side until the early 50s. Dr. Rivera revealed accounts by WWII and Korean War veterans who, upon their return from duty, felt empowered and entitled as Americans because of their service and sacrifice.

It was WWII veteran Ralph Cervantes who sued the local government after he was banned from buying a house near Colton Jr. High. The case was tied up in court for years, but the purchase was eventually granted. The precedent was set and resulted in a migration of Mexican-Americans to the north side. As a result, Dr. Rivera noted, over 90% of Colton today is Mexican. Additionally, it wasn’t until 1948 that Colton had its first Mexican city councilman; the city was chartered in 1877.

Despite the racist climate, a common sentiment among those interviewed was the sense of connection among the community. “Many spoke about how wonderful it was to grow up in a segregated community, because it was self contained, we had our own schools, stores, restaurants,” Dr. Rivera remarked. “Segregation was one of the strengths of the community because we had to rely on each other.”

Vásquez, whose great-grandparents settled in South Colton, fondly recalled the Fiestas Patrias, and opined that people stay in Colton because of the family bond. “People want to be close to relatives and there’s a certain amount of comfort being in a familiar (setting).”

It was that sense of belonging and community that led Dr. Rivera and his young wife Dr. Lily Rivera to return to Colton after they graduated from college. Despite their degrees and careers as educators, their rental application for an apartment was denied.

“It’s important that we share the history with our kids, that these things did happen and if we’re not careful enough, it might happen again,” Dr. Rivera cautioned.

Dr. Rivera, Acosta and Vásquez continue to conduct oral interviews, and hope the South Colton Oral History Project, a collaborative effort of the Pfau Library, California Humanities Foundation and the Colton Area Museum, will be included in the Colton school curriculum in the future.

The interviews can be accessed at http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/colton-history.